I embarked on my next task in historic painting methods by tackling the very ground that my art would go on. “Ground” in art terms usually means the surface that gets worked on, most commonly canvas or wood panel. I decided that if I was already going down the rabbit hole of historic painting, I might as well lean into it and start from the ground up. Paint rarely goes directly onto a canvas or paper without the surface first being primed with a ground to help protect it. Surfaces like canvas, wood, and paper are all porous and will absorb the paint, and oil paints and enamel paints can corrode these surfaces, unless a proper barrier is in place. Any sort of water-proofing or skin-forming layer would do, and now acrylic gesso is fairly standard for panels and canvases. However, rabbit skin gesso used to be the old stand-by for many many years.

Most old recipes for rabbit skin gesso consist of rabbit skin glue and lead white pigment or whiting. Rabbit skin glue, or any animal hide glue, is a collagen-based glue made from soaking skins in water to extract the strong proteins which form strong, water-proof bonding once dried. Believe me, I wanted to find real, genuine rabbit skin and soak it, and really do the whole process right. However, in today’s society? I’m not really sure where one would go to obtain some rabbit skins legitimately. So, I settled for powdered rabbit skin, which is commercially available and functions on the just-add-water principle. Simple and easy.

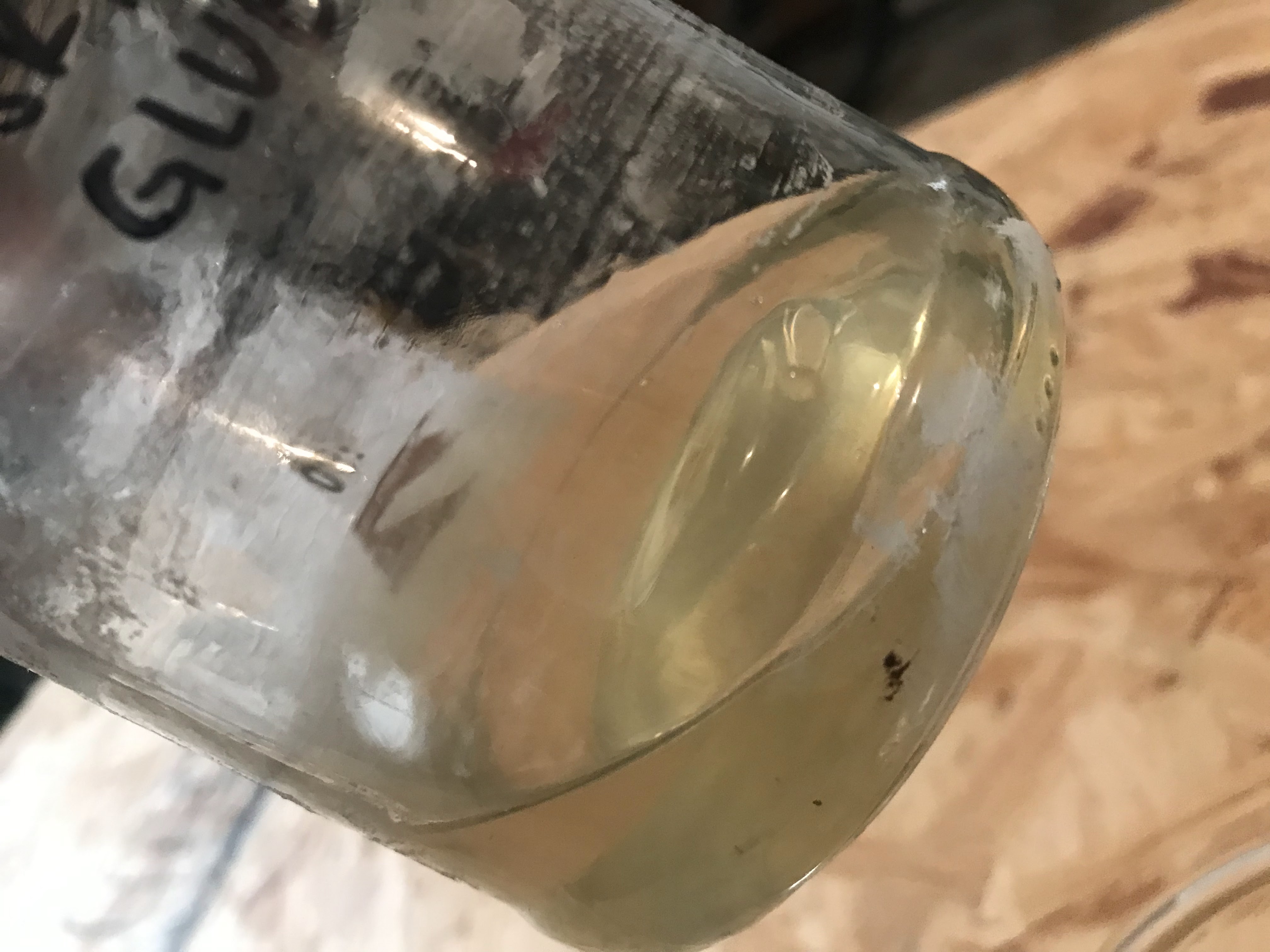

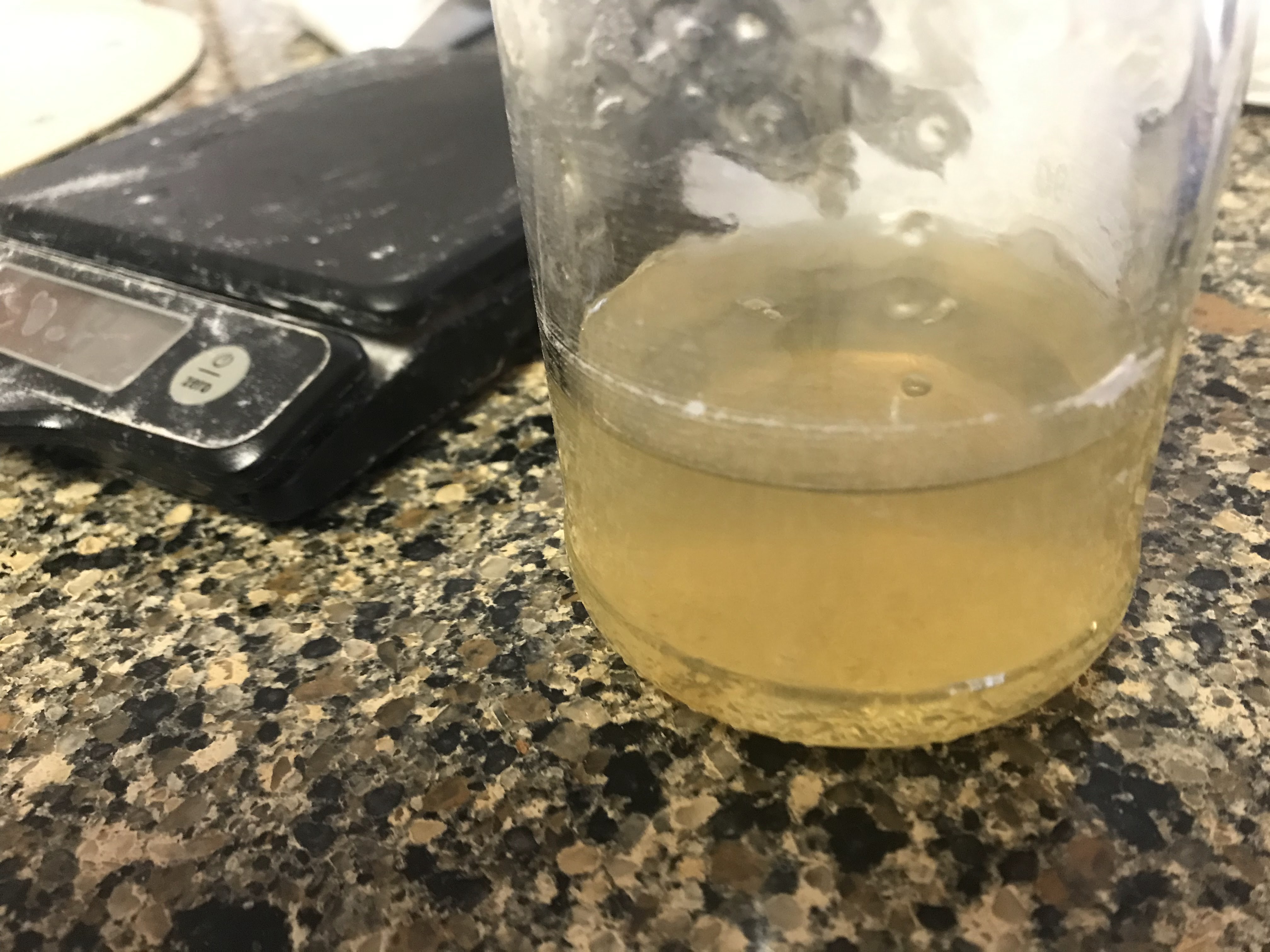

I dissolved the powdered rabbit skin in boiling water. Temperature definitely played a big role in this experiment, and I tried my best to stay on top of it. After the powder dissolves, the glue stays liquid while it is hot, and the glue solidifies at room temperature. It can be reheated and reliquified.

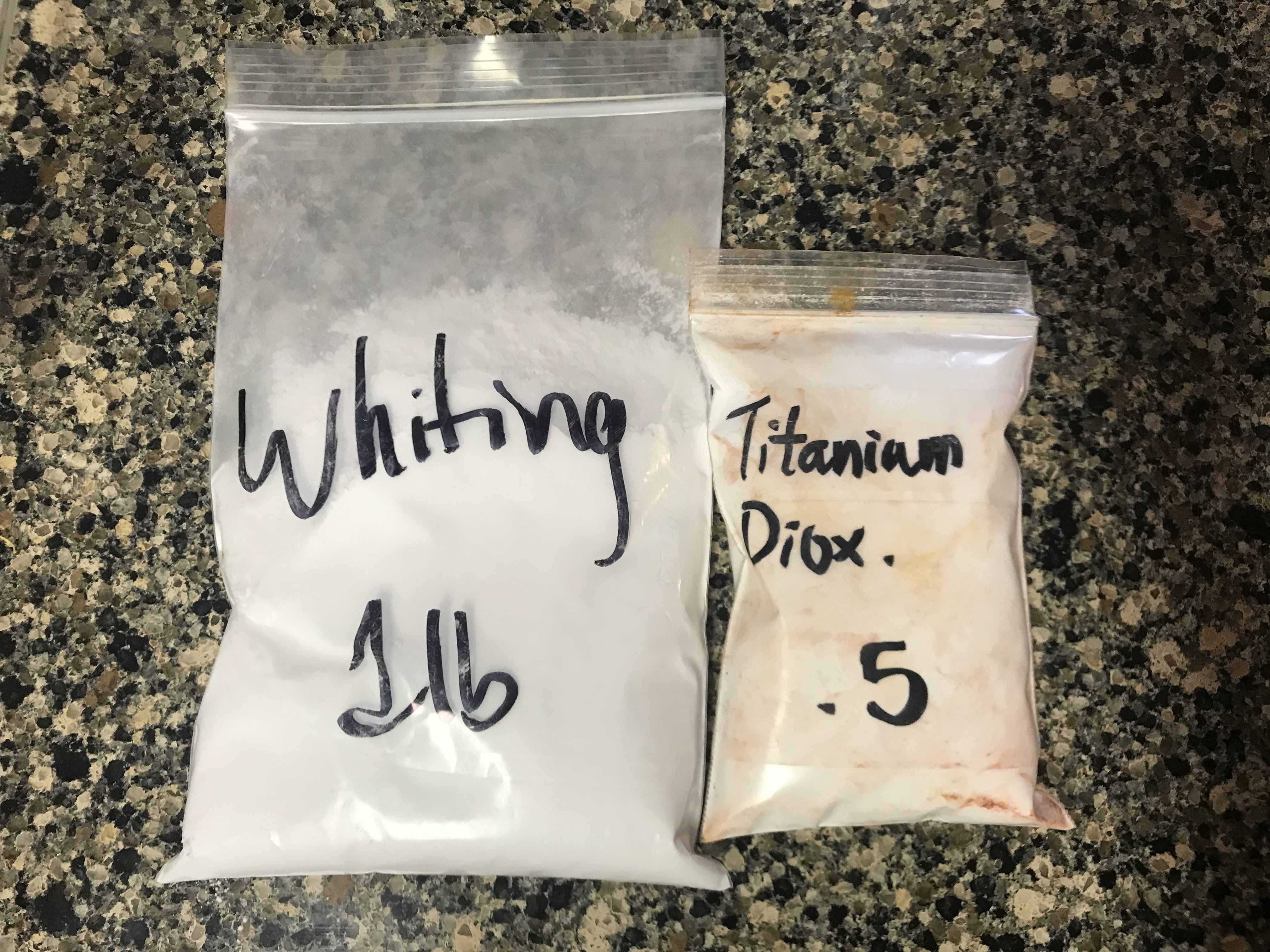

I should have only used whiting as the pigment because using nicer pigments feels like a waste when the gesso will be completely covered up by the painting. The gesso recipe that I followed used titanium white (in replacement of lead white) and whiting in equal parts. Titanium white has better brilliance than whiting, so I get why it would be included. Honestly though, the gesso will get covered anyways, so I see little use in including a good white pigment in the gesso. Going forward, I plan on just using whiting.

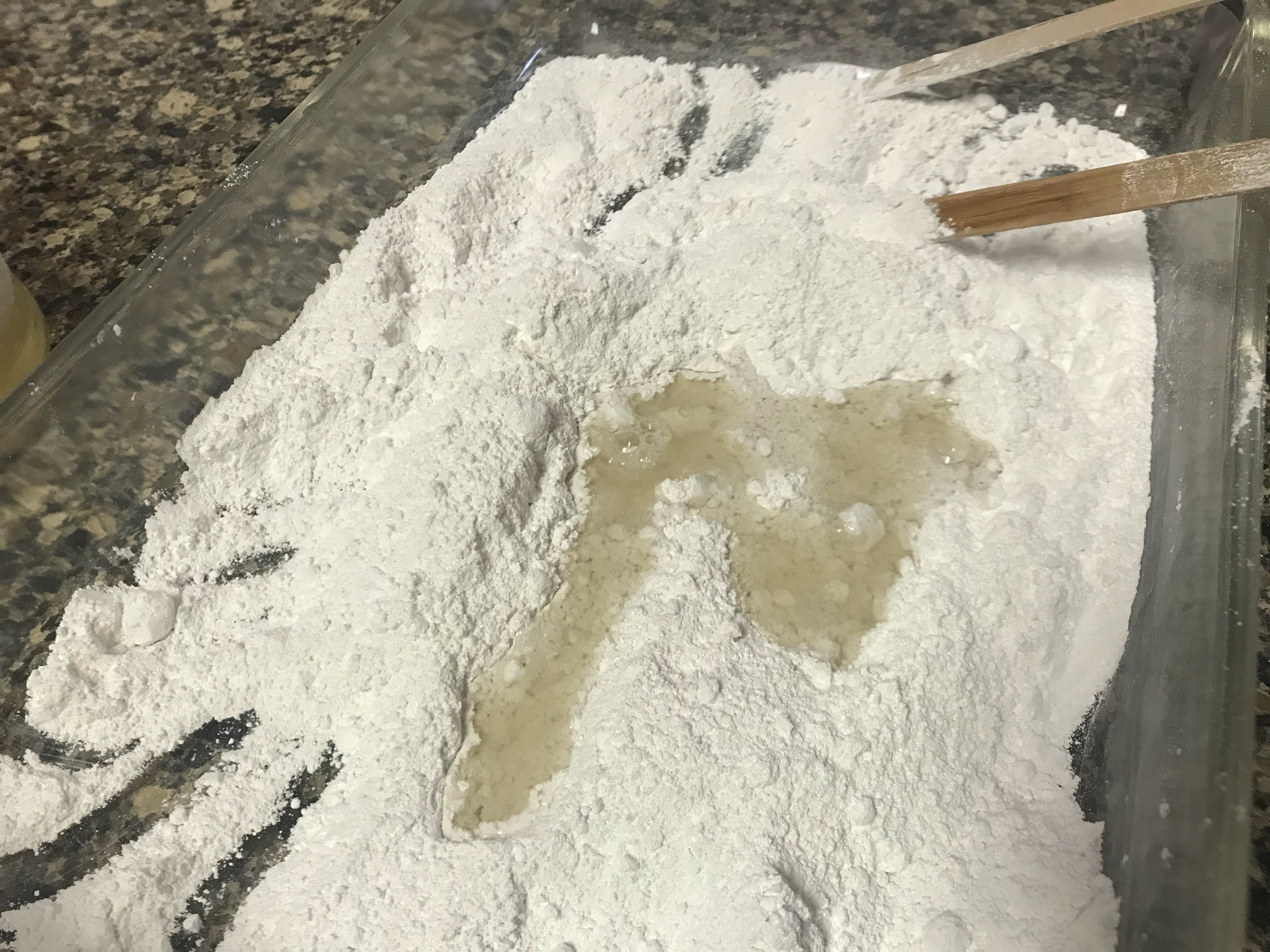

The recipe I followed also said to add all ingredients into a dish and then use a muller to incorporate everything, similar to mulling down paint. I tried this at first, and it was incredibly inconvenient and messy. The process took a while and still had some unmixed chunks of dry pigments. Later in my project, I needed to make a second batch of gesso, and I did what I think most reasonable people would do, which is throw all the components in a jar and shake it like it’s Bisquik batter on Saturday morning. The jar method proved to be the best strategy, it was clean, quick, and efficient. The rabbit skin glue does need hot water to be mixed, so there is an element of danger in holding and shaking hot water to beware of.

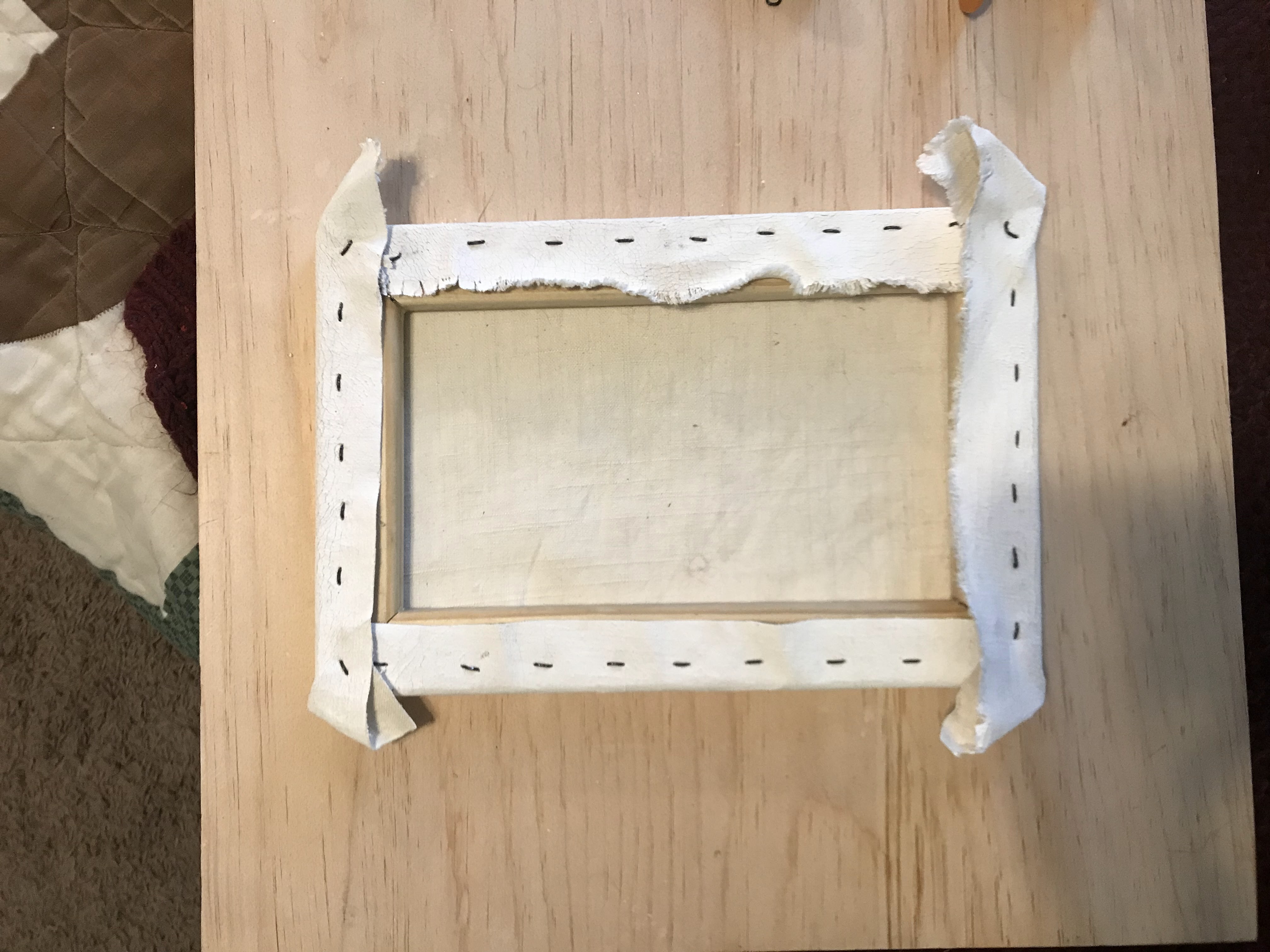

In my pursuit of frugality, I found some canvas from a fabric consignment shop. The canvas was probably too lightweight and not completely suitable for my purposes, but I went on ahead anyways.

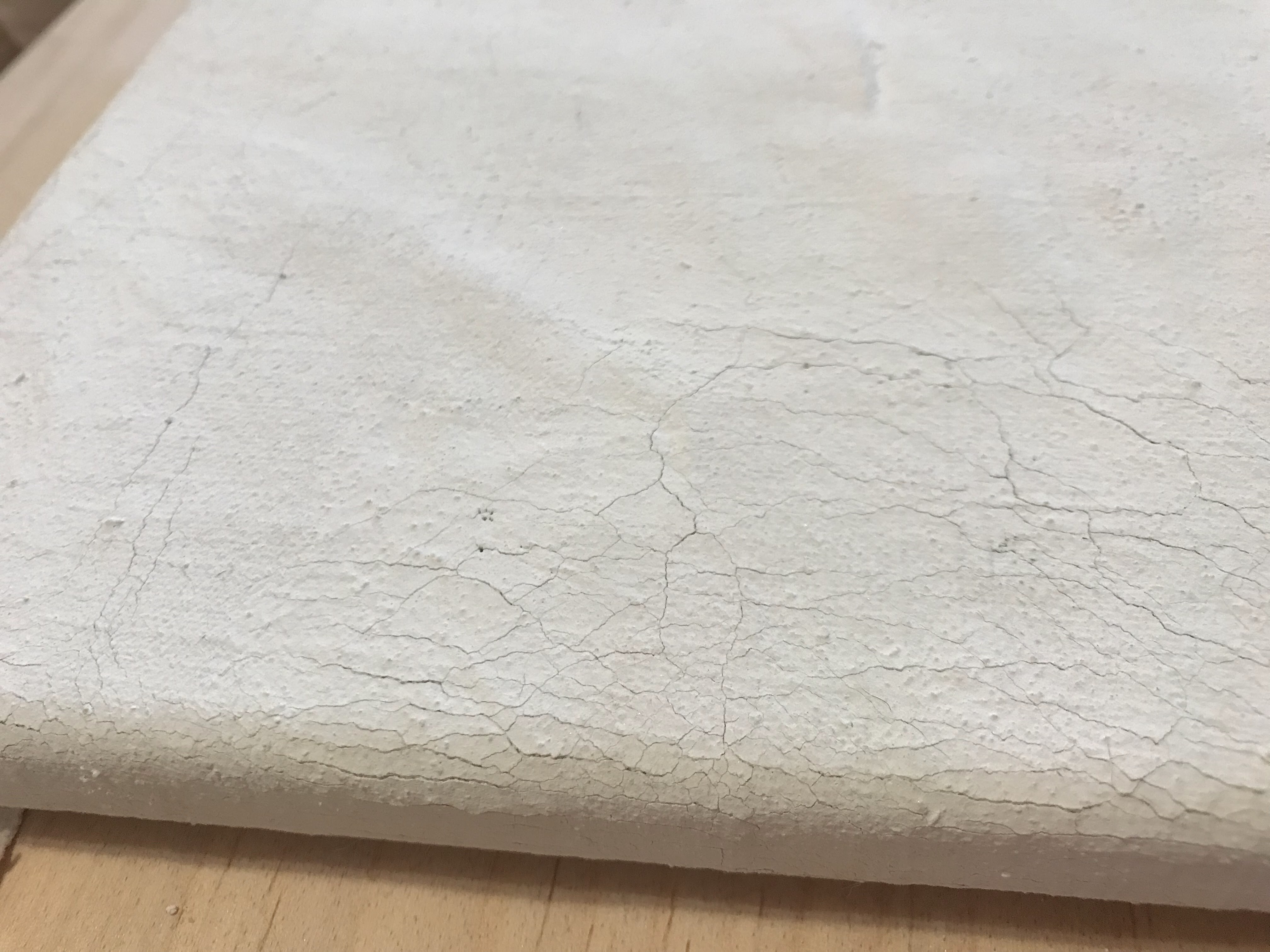

I kept the gesso in a bath of hot water in an attempt to keep it loose and liquid, but as the water temperature changed between the water cooling and me adding in hot water, the consistency of the gesso fluctuated and was unfortunately inconsistent across the canvas. The fibers of the canvas were also relatively loose and would stretch at inconsistent rates and then get locked in varying stretched states as the gesso dried.

Once the gesso was fully applied and dry, I tried to stretch a canvas with what I made. It was immediately obvious that the gesso had been applied too thickly in some areas and would crack. As always, I just went ahead and tried to make it work anyways. I made the canvas frame from some pine furring strips. I used awful staples and more rabbit skin glue to construct the frame. Then, I cut out a section of canvas and stretched it like any other canvas. It cracked a lot.

I think the canvas can be salvaged and painted on, but my diagnosis of the situation is that the canvas was too thin and the rabbit skin gesso was not warm enough consistently. I will have to source better canvas and work in smaller gesso batches. Experimentation is all about living and learning, right?